-

Haiti police, civilians kill 28 gang members: authorities

Haiti police, civilians kill 28 gang members: authorities

-

Taxing the richest: what the G20 decided

-

'Minecraft' to come to life in UK and US under theme park deal

'Minecraft' to come to life in UK and US under theme park deal

-

IMF, Ukraine, reach agreement on $1.1 bn loan disbursement

-

Japan on cusp of World Cup as Son scores in Palestine draw

Japan on cusp of World Cup as Son scores in Palestine draw

-

Chelsea condemn 'hateful' homophobic abuse towards Kerr, Mewis

-

Hamilton to race final three grands prix of Mercedes career

Hamilton to race final three grands prix of Mercedes career

-

Gatland has not become a 'bad coach' says Springboks' Erasmus

-

Slovakia take Britain to doubles decider in BJK Cup semis

Slovakia take Britain to doubles decider in BJK Cup semis

-

Brazil arrests soldiers over alleged 2022 Lula assassination plot

-

Ukraine war and climate stalemate loom over G20 summit

Ukraine war and climate stalemate loom over G20 summit

-

Ukraine fires first US long-range missiles into Russia

-

Retiring Nadal to play singles for Spain against Netherlands in Davis Cup

Retiring Nadal to play singles for Spain against Netherlands in Davis Cup

-

Rain ruins Sri Lanka's final ODI against New Zealand

-

Stocks sink on fears of Ukraine-Russia escalation

Stocks sink on fears of Ukraine-Russia escalation

-

Hendrikse brothers start for South Africa against Wales

-

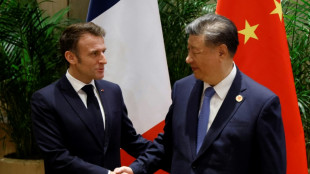

Macron tells Xi he shares desire for 'durable peace' in Ukraine

Macron tells Xi he shares desire for 'durable peace' in Ukraine

-

Ruthless Japan beat China to move to brink of World Cup qualification

-

French farmers threaten 'chaos' over proposed EU-Mercosur deal

French farmers threaten 'chaos' over proposed EU-Mercosur deal

-

Brazil arrests G20 guards over alleged 2022 Lula assassination plot

-

China's Xi urges 'strategic' ties in talks with Germany's Scholz

China's Xi urges 'strategic' ties in talks with Germany's Scholz

-

Raducanu gives Britain lead on Slovakia in BJK Cup semis

-

Russia says Ukraine fired first US-long range missiles

Russia says Ukraine fired first US-long range missiles

-

COP29 negotiators strive for deal after G20 'marching orders'

-

Walmart lifts full-year forecast after strong Q3

Walmart lifts full-year forecast after strong Q3

-

British farmers protest in London over inheritance tax change

-

NATO holds large Arctic exercises in Russia's backyard

NATO holds large Arctic exercises in Russia's backyard

-

Trouble brews in India's Manipur state

-

Son of Norwegian princess arrested on suspicion of rape

Son of Norwegian princess arrested on suspicion of rape

-

Romanian court says 'irregularities' in influencer Andrew Tate's indictment

-

Iran faces fresh censure over lack of cooperation at UN nuclear meeting

Iran faces fresh censure over lack of cooperation at UN nuclear meeting

-

Despondency and defiance as 45 Hong Kong campaigners jailed

-

Scholar, lawmakers and journalist among Hong Kongers jailed

Scholar, lawmakers and journalist among Hong Kongers jailed

-

European stocks slide on fears of Russia-Ukraine escalation

-

Police break up Georgia vote protest as president mounts court challenge

Police break up Georgia vote protest as president mounts court challenge

-

Spain royals visit flood epicentre after chaotic trip

-

France's Gisele Pelicot says 'macho' society must change attitude on rape

France's Gisele Pelicot says 'macho' society must change attitude on rape

-

G20 leaders talk climate, wars -- and brace for Trump's return

-

US lawmaker accuses Azerbaijan in near 'assault' at COP29

US lawmaker accuses Azerbaijan in near 'assault' at COP29

-

Tuchel's England have 'tools' to win World Cup, says Carsley

-

Federer hails 'historic' Nadal ahead of imminent retirement

Federer hails 'historic' Nadal ahead of imminent retirement

-

Ukraine vows no surrender, Kremlin issues nuke threat on 1,000th day of war

-

Novo Nordisk's obesity drug Wegovy goes on sale in China

Novo Nordisk's obesity drug Wegovy goes on sale in China

-

Spain royals to visit flood epicentre after chaotic trip: media

-

French farmers step up protests against EU-Mercosur deal

French farmers step up protests against EU-Mercosur deal

-

Rose says Europe Ryder Cup stars play 'for the badge' not money

-

Negotiators seek to break COP29 impasse after G20 'marching orders'

Negotiators seek to break COP29 impasse after G20 'marching orders'

-

Burst dike leaves Filipino farmers under water

-

Markets rally after US bounce as Nvidia comes into focus

Markets rally after US bounce as Nvidia comes into focus

-

Crisis-hit Thyssenkrupp books another hefty annual loss

| CMSC | -0.06% | 24.61 | $ | |

| RBGPF | -0.74% | 59.75 | $ | |

| AZN | 1.08% | 64.085 | $ | |

| SCS | -1.11% | 13.055 | $ | |

| BCC | -1.82% | 139.01 | $ | |

| RIO | 0.08% | 62.17 | $ | |

| GSK | -0.88% | 33.395 | $ | |

| NGG | 0.96% | 63.51 | $ | |

| BCE | 0.75% | 27.435 | $ | |

| CMSD | -0.08% | 24.371 | $ | |

| RYCEF | -2.54% | 6.68 | $ | |

| BP | -1.33% | 29.035 | $ | |

| JRI | -0.09% | 13.218 | $ | |

| BTI | 0.45% | 36.845 | $ | |

| RELX | 0.46% | 45.25 | $ | |

| VOD | -0.06% | 8.915 | $ |

On patrol with Kharkiv's elite 'Spetsnaz' police force

Shouts, the doors are kicked down and a window smashed. In a matter of seconds, the hotel is surrounded and its occupants find themselves on the ground, wrists tied, or with their hands against the wall and a Kalashnikov in the small of their back.

In Ukraine's second city, Kharkiv, the police special forces -- or "Spetsnaz" -- are searching for a group of suspected "saboteurs" working for the Russian invaders behind Ukrainian lines.

The four visitors with harsh faces and tattooed arms who arrived at this guesthouse the previous day caught the eye of security services. They are taken away unceremoniously to "verify their identities".

With the Russian army parked at Kharkiv's gates, the aim of the Spetsnaz is to try and "maintain order and protect the population" amid the chaos.

More than 1.5 million live in the majority Russian-speaking city, which has been regularly shelled by President Vladimir Putin's troops through their five weeks of offensive.

AFP was able to accompany these special forces -- akin to an American SWAT team -- on patrol during the city's night-time curfew.

First stop: a petrol station in the district of Saltivka hit by a rocket.

The truck speeds through the deserted streets towards the flames, which reach several metres into the air. The elite police squad travels in a bulky white van that until a few weeks ago served to ferry cash.

Wearing balaclavas and helmets, and strapped into their bulletproof vests, they keep a good distance from the blaze. There are no victims, it seems, and "the fire department are on their way", says Valery, "24 years in the force" and head of the patrol.

- Suspicious activity -

Valery points at the apartment buildings opposite with the beam of the torch strapped to the barrel of his AK-47, all of them apparently empty.

A third of Kharkiv's inhabitants have fled the city since the start of the war, according to authorities, especially in the northeastern areas of the city most exposed to Russian attacks.

"In the first two weeks of the war there were a lot of saboteurs that tried to get into the city from all over. Now there are very few," the redheaded commander says. "But there could still be spies who give the Russians our forces' coordinates to strike them."

A flash of red light excites the patrol, potentially a "laser" from a precision weapon. But having checked with night-vision goggles, it turns out to be a false alarm.

The team moves on, keeping their eyes peeled for any suspicious activity.

Almost no one is on the road at night in Kharkiv apart from a few solitary police cars which flash their blue lights when they approach the special forces van. In any case, "nobody is allowed to move around without the password".

A dilapidated car with its warning lights on pokes out from a side street. The patrol immediately holds up the vehicle, brusquely pulling the two passengers out to interrogate them.

The driver says he wanted to "take his wife back" to somewhere unclear. Both seem a little tipsy. The car is allowed to go and parks up on the pavement, and some swearing is heard. The pair did not seem to be up to anything untoward.

- 'Holding the rear' -

"The army is on the front line, we're holding the rear. We're maintaining order in Kharkiv and protecting citizens," says Valery. "If we weren't here then the army would be weaker."

"When there is an explosion or a fire we help with the evacuation of the injured, to secure the perimeter, to take families to safety."

"Our job is one hundred times more important during a war," Valery says.

"Primarily, we're an intervention group in charge of arrests," says Sergei, an engineer by training.

One last detour through a park on a hill "where young lovers liked to come before the invasion", Valery says, suddenly showing a softer side.

"Look, not a single light, almost every window is dark," he says. "I've never seen my city so quiet and sad."

Several loud explosions in a nearby neighbourhood tear through the silence. Valery's head turns sharply to the sky: "Watch out! Incoming!"

On that day, 380 rockets rain down on Kharkiv, along with a further 50 or so shots fired from tanks and mortars, according to authorities.

"Today, we're helping the population of a city at war," he says. "It's an important job, no? Being a Spetsnaz, it's not just a word, you have to be up to it, even when it comes to helping people under fire."

B.Torres--AT